Disc Herniations

Herniated disc

Herniated discs are the most common cause of back pain and leg pain (“sciatica”) and the second most common reason for visits to physician. The disc is made up of a gelatinous center (uucleus pulposis) surrounded by a tough ring of fibrous tissue, much like the tire tread surrounding tube.

The disc provides motion between each spine bone (vertebrae) and functions as a shock absorber in normal individuals while the tough, fibrous annulus stabilizes this motion segment and resists torsional forces. With aging or trauma a tear or rent can develop in the annulus and a piece of the gelatinous nucleus pulposis can protrude into tor through this defect producing a “disc herniation.” Disc degeneration and herniation are the most common cause of back pain and “sciatica” (leg pain) and one of the most common reasons for visit to a physician.

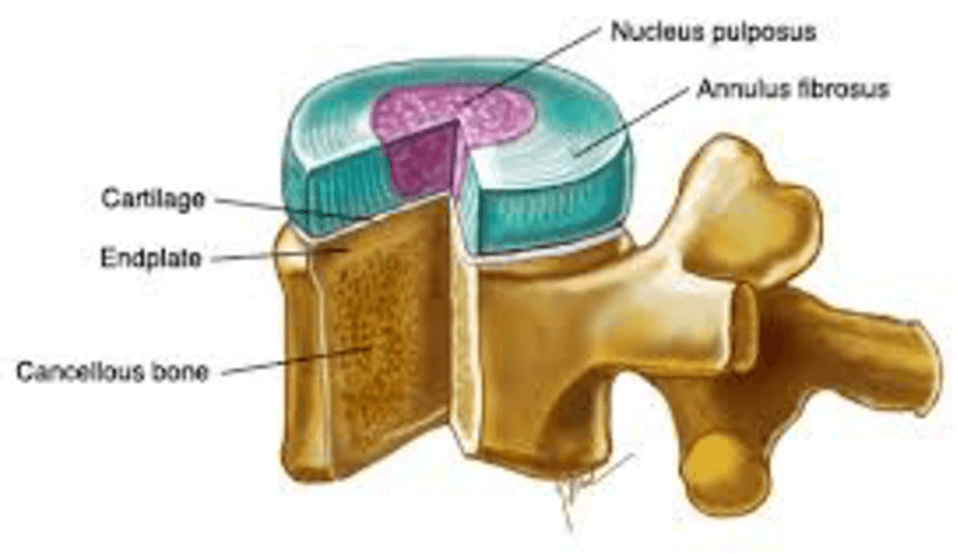

Figure 1

Cross section of a “vertebral segment” consisting of a lumbar disc (which, in combination with two posterior facet joints, provides motion to the spine) and its adjacent vertebral bone.

Causes

Disc herniations most commonly occur in adults between the ages of 20-60 and usually involve the low back although they also occur in the neck and less frequently the trunk (thoracic spine). They are thought to be the result of “wear and tear” and usually follow some bending, lifting, or twisting injury. Environmental factors include professions that involve heavy lifting or torsional stress and motor vehicle driving. Some studies have demonstrated a genetic predisposition for herniated discs and these individuals are more likely to have multiple herniations, chronic pain, and surgical treatment.

Symptoms and diagnosis

Most herniations begin with small tears of the tough fibrous annulus which allow portions of the nucleus pulposis to herniate or protrude through theses tears.

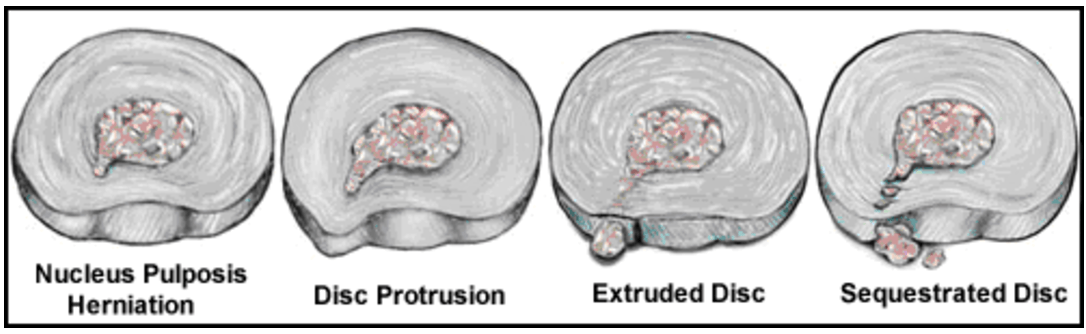

Figure 2

Schematic representation of disc injury beginning with small annular tear or fissure and progressing to disc protrusion, disc extrusion, and sequestration of a free fragment into the spinal canal.

With further degeneration or injury a complete tear of the annulus may occur permitting the nucleus pulposis to extrude outside of the annulus or

even break off a free disc fragment (sequestered disc) into the spinal canal. The most common complaint is low back pain from the torn annulus aggravated by activities that stress the disc, such as bending, twisting, and prolonged sitting, especially in moving vehicles, coughing and sneezing.

The disc herniation can also compress and inflame nearby nerves causing “sciatica” or radicular leg pain. Most commonly patients describe pain in the right or left lower back and buttocks with radiation of a deep aching pain into the leg and foot, sometimes into the thigh. More severe nerve involvement might result in numbness, tingling, weakness, and cramping in any region the affected nerve travels. In addition to these mechanical symptoms, the disc also contains inflammatory proteins that chemically irritate the nerves and accentuate and prolong these symptoms.

A thorough history and physical examination with an experienced doctor is usually sufficient to make a diagnosis in the majority of patients which can be confirmed with imaging study. MRI remains the gold standard although CT exam is sufficient for those who are unable to undergoe an MRI (for example, a patient with cardiac pacemaker or cerebral coil used to treat an aneurysm).

Treatment

There are a wide range of treatments advocated for the herniated disc. Fortunately, the majority of these conditions will respond to a short period of rest, followed by activity modification, anti-inflammatories, and gradual resumption of activities. Patients with neurologic symptoms or those with significant pain likely will benefit from further evaluation and treatment. This may include pain medication, physical therapy, epidural steroid injections and education. Aerobic exercise conditioning is the best predictor for long term improvement and function. Many other treatment modalities have been described including chiropractic care, acupuncture, ultrasound and tens therapy with varying results.

Surgical treatment is an excellent alternative for those patients who have continued pain despite non-operative treatment as it definitively removes the neurologic compression and inflammatory nidus.

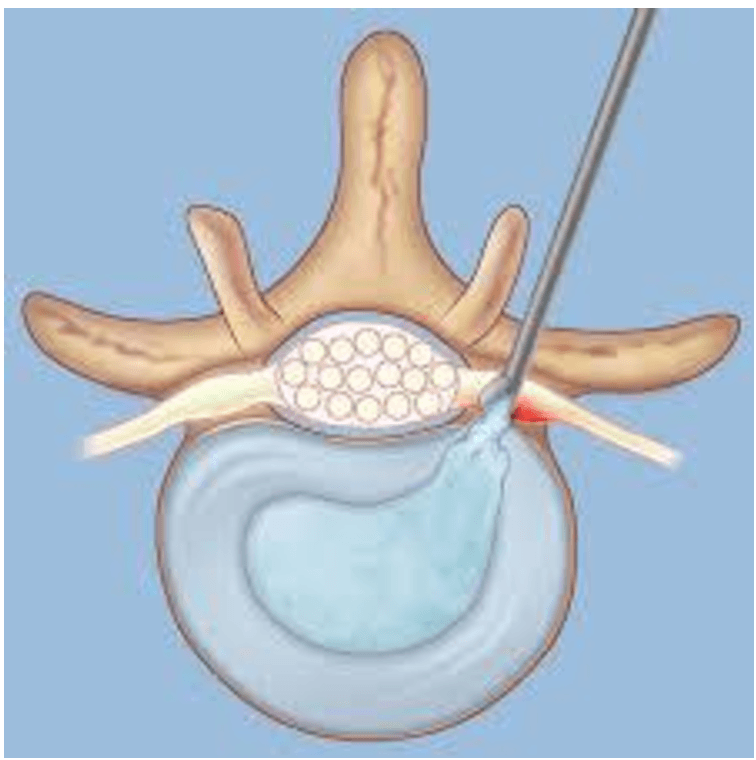

Figure 3

Illustration of a microscopic discectomy in which the offending herniated disc is surgically removed decompressing the nerve and resolving “sciatica” or radicular leg pain.

In the only randomized comparison of non-operative and operative treatment, surgical patients were significantly better at 1yr (with 26% crossover of non-operative patients) although these differences disappeared at 10 year follow-up (1). Surgery should be considered for all patients with acute and dense motor deficits and is emergently necessary in the presence of bowel and bladder dysfunction (cauda equina syndrome). Snce Mixter and Barr’s classic report in 1934 (2), open disc excision has become the most commonly performed spinal surgery and remains the gold standard with high (90%) patient satisfaction.

Microdiscectomy using magnification loupes or a microscope was popularized in the late 1970’s. It involves a smaller exposure with less soft tissue dissection and studies have shown faster recovery and return to work with improved patient outcomes (3,4). Indications are patients with predominant leg pain, a positive straight leg raise, and imaging studies confirming compression at the symptomatic level. The principles of surgical treatment are decompression and mobilization of the affected neural elements and removal of the herniated fragment. This typically includes release of the ligamentum flavum, partial laminotomy, and medial facetectomy. The neurologic structures are dissected off the disc with a Penfield elevator exposing the underlying non-contained herniation which is then removed. Contained herniations require an annulotomy before the disc fragment can be identified and removed.

More recently, minimally invasive spine surgery (MISS), using endoscopic techniques have allowed discectomy to be performed safely and effectively as an ambulatory procedure with results superior to other outpatient therapies (chemonucleolysis, percutaneous discectomy, and thermal coagulation).

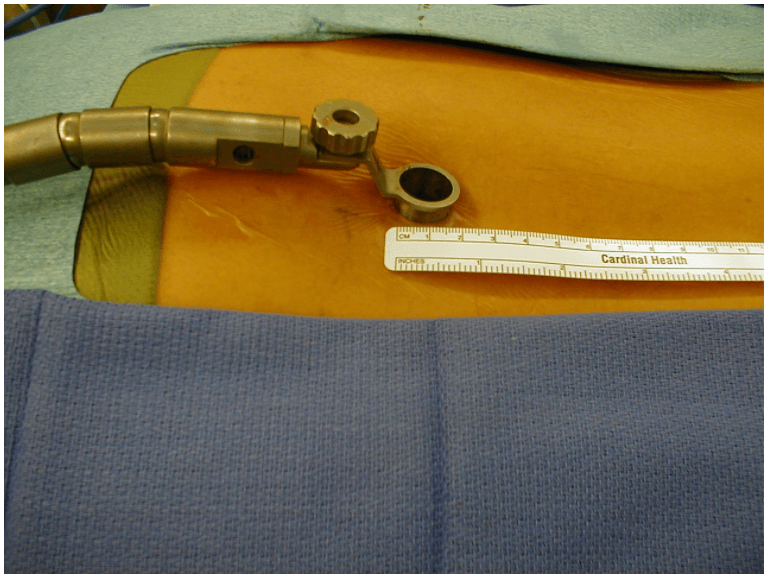

Figure 4

An example of a microscopic discectomy performed through “endoscopic” retractor which allows for less soft tissue dissection and faster recovery.

The endoscopic technique allows a limited exposure through an 18mm tubular retractor with an average length of stay of 31/2 hours (Figure 1).

Results compare favorably to microdiscectomy with 72% of patients experiencing complete relief and 20% experiencing minimal discomfort requiring no further treatment (5). Complications include infection, durotomy, nerve root injury, recurrent disc heniation, and chronic back and/or leg pain. Rarely, patients develop far lateral compression of the nerve root in the foramen which may be approached directly through a lateral approach as described by Wiltse (6).. Recent studies demonstrate the superiority of surgical treatment compared to non operative management in relieving symptoms and improving function and these results persisted through long term follow up (4yrs)(7).

Further information:

Herniated Lumbar – Patient Handout (PDF)

Case 14: 38 yo with sciatica and L5/S1 HNP

Case 16: 46 yo male with C6/7 HNP and radicular arm pain

References

- Weber H. Lumbar disc hernistion. A controlled, prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine 1983;8:131-140.

- Mixter WJ, Barr JS. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med 1934; 211:210-215.

- Caspar W. A new surgical procedure for lumbar disc herniation causing less tissue damage through microsurgical approach. Adv Neurosurg 1977; 4:74-79.

- Williams RW. Microlumbar discectomy: A conservative surgical approach to the virgin herniated lumbar disc. Spine 1978; 3:175-182.

- Hilton DL Microdiscectomy with minimally invasive tubular retractor. Outpatient Spinal Surgery 2002 171-195.

- Wiltse LL, Bateman JG, Hutchinson RH, et al. The paraspinal sacro-spinalis approach to the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop 35:80, 1964.

- Weinstein JN, Lurie JD, Tosteson TD, et al. Surgical vs nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation. Spine 2008; 33,25: 2789-2800.